When lawmakers in Des Moines are seriously discussing rolling back laws against child labor, it can be hard to believe there’s anything positive about the state of labor in Iowa. But despite years of Republicans raging against unions, union membership in Iowa slightly increased last year. In 2021, 6.5 percent of the state’s workers were in unions. In 2022, it grew to 7 percent.

If that number seems low, it’s worth remembering that in 1947 — 70 years before Republicans in the 2017 Iowa Legislature gutted collective bargaining rights for public sector unions, except police and other public safety unions — Iowa became the first state outside the deep south to pass a right-to-work law, undermining the ability of unions to organize workplaces.

Beyond that small uptick in union membership, there were a few other bright spots recently.

John Deere workers succeeded in getting a decent contract after a 34-day-long strike last year. In January, workers at Ingredion in Cedar Rapids brought a 175-day strike to a successful conclusion. A few days later, Case-New Holland workers in Burlington ratified a new contract after eight months on the picket line. And at the end of March, it was announced that workers at the downtown Starbucks in Iowa City were joining the fast-moving labor organizing effort in the country, and had taken the first steps required to form a union, the first at a Starbucks in Iowa.

It’s not surprising those bright spots are hard to see. Every big newspaper in the country has a Business section; none have a Labor section. The gyrations of the stock market, even when clearly irrational, are treated like a reliable sign of the national economy’s health, while decades of wage stagnation and the yawning wealth gap between the working class and those living off investment income aren’t.

Labor history is scantily covered in American history textbooks, and any discussion in Iowa schools of class conflict in the country’s labor disputes, current or historical, might run afoul of the ban on teaching “divisive concepts” that Gov. Kim Reynolds signed into law in 2021.

The political climate in America for the last 40 years has been unhealthy for the labor movement. Republicans have done almost everything possible to oppose unions (except police unions), while the Democratic Party has been a half-hearted ally for unions since the ’80s (except for police unions).

The “erasure of workers from our collective sense of ourselves as Americans is a political act,” labor historian Erik Loomis wrote in his 2018 book Strike! “Americans’ shared memory,” shaped by school textbooks, the media and the stories we celebrate in public settings “too often erases or downplays critical stories of workplace struggle.”

Even Labor Day contributes to this erasure. Congress made it a holiday in 1894 to discourage Americans from participating in the annual international celebrations of labor unions on May 1. It worked.

May Day, which grew out of commemorations of the brutal repression of an 1886 strike in Chicago, is celebrated worldwide, but it’s largely ignored in America. And Labor Day has little meaning to most people beyond a nice, long weekend in late summer.

Most Americans regard the eight-hour workday, the 40-hour workweek and basic health and safety laws in the workplace as if they were naturally occurring phenomena, instead of victories won by unions after long and bitter struggles with employers and politicians.

Given all this, it’s no wonder so few Iowans know that 112 years ago, Muscatine was briefly the most important city in America for labor organizers.

Muscatine owes its place in labor history to clams. It was the plentiful supply of freshwater clams along the Mississippi River at Muscatine that convinced John Boepple, an immigrant from Germany, to settle there in 1891. Boepple used the mother of pearl lining in clam shells to make buttons he sold as “pearl buttons.” He opened a small factory in Muscatine shortly after moving there, where he and his assistants made the buttons using hand tools. Pearl buttons quickly became fashionable.

As the buttons became more profitable, the work was mechanized and factories proliferated. By 1901, there were 27 pearl button factories in Muscatine. Ten years later, there were 43. Only New York produced more pearl buttons than Iowa, and Muscatine was the state’s button capital.

The button factories were by far the city’s largest employers. Everyone in Muscatine either worked in a factory or knew someone who did.

Working conditions appalled and horrified observers who visited the factories. Before being cut, the shells had to be softened by soaking them in water. Cutting rooms had barrels of standing water filled with shells that turned the water rancid. In addition to the stench, the water was also toxic, causing cuts on hands to become infected. And there were plenty of cuts on workers’ hands. A complete lack of safety guards on the machinery made mangled hands and missing fingers common.

Work in the factories was segregated by sex. Men cut the button blanks from shells, a process that filled the air in the poorly ventilated factories with dust that caused breathing problems. Women operated the machines that drilled holes into the buttons and embossed patterns on them. But most women worked sorting buttons by size and sewing them onto cards.

Workers were paid by the piece. For sewing 168 buttons onto cards, women were paid one-and-a-half cents. What few laws existed to protect workers were routinely ignored, including those prohibiting child labor.

There were failed attempts to unionize Muscatine button workers in 1897 and 1903. But in 1910, things began to change.

That year, there was a major strike by garment factory workers in Chicago. Its effects were felt in Muscatine in two ways. First, the example of workers standing up for better treatment was inspiring. Second, with fewer garments being produced, demand for buttons decreased. Production was cut in the Muscatine factories, and so were wages.

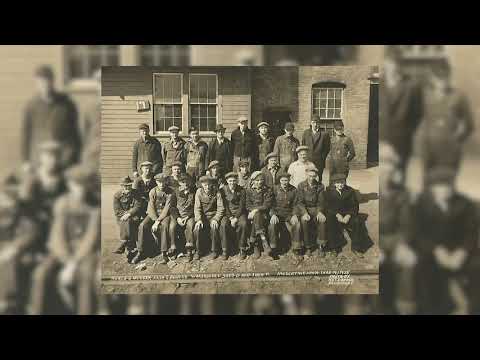

In November 1910, nine men and 29 women formed the Muscatine Button Workers Protective Union (BWPU). Factory owners and managers derided the organizing effort, but membership grew quickly. By February, the BWPU had almost 2,500 members. It was the largest union in Iowa. The attitudes of owners and managers changed.

On Feb. 25, 1911, almost all of Muscatine’s button factories, including all of the largest ones, suddenly shut down. Owners claimed the closings weren’t coordinated and had nothing to do with the new union. They cited national economic conditions as the cause. But two weeks later, the factories reopened with only nonunion workers. BWPU members were locked out. The union declared a strike, and called for a boycott.

The BWPU was affiliated with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which had started by organizing craft labor and had only relatively recently, and somewhat reluctantly, begun to organize factory workers. But the strike in Muscatine was different from other industrial labor actions.

A large percentage of factory workers in early 20th century America were immigrants for whom English was a second, often difficult, language. Xenophobic and racist imagery colored how other Americans viewed those workers, and since Jewish workers were often prominent among union organizers, antisemitism joined the other fears and prejudices. Major newspapers and national political leaders portrayed unions as the work of dangerous subversives determined to undermine American business and society.

Muscatine broke that mold. The striking workers were unambiguously white, overwhelmingly American-born and from the sort of rural communities Americans romanticized as repositories of wholesome values. National labor leaders saw a chance to change the public image of industrial unions.

The AFL sent a top official to negotiate on behalf of the BWPU. Factory owners remained united in rejecting any deal that recognized the union. Leaders from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the AFL’s biggest rival for organizing workers, also came to Muscatine to observe the strike. Newspapers around the country carried stories on the strike when it began.

Women in the BWPU took the lead on relief efforts to make sure striking workers and their families had food and other basic necessities. That work was made easier by support from the broader community, with many people recognizing the strikers as their friends and neighbors.

Community support, however, faded as the strike dragged on for 15 months.

In retrospect, it’s remarkable the strike in Muscatine lasted into 1912. As Loomis documents in his book, “There is simply no evidence from American history that unions can succeed if the government and employers combine to crush them.”

A month into the Muscatine strike, as fights between strikers and scabs became common, factory owners hired professional strike-breakers from Chicago and St. Louis. Known as “sluggers,” because they attacked strikers with baseball bats, the goons were sworn in as “special deputies” by the sheriff.

In April, the sluggers’ actions sparked a riot in the city. The special deputies left town, but the governor sent in three companies of state militia, who occupied Muscatine for three days.

Gov. Beryl Carroll also tried to impose a settlement in the strike, drafting his own proposed contract. But the BWPU rejected it, saying the terms of the contract were too vague to be effective. In the autumn of 1911, Carroll sent in the militia again.

In her study of the strike published in Annals of Iowa, Kate Rousamaniere explains it’s hard to reconstruct exactly what went on in the strike, because the “Muscatine News-Tribune, which was sympathetic to the union in the first three months of the strike, abruptly stopped coverage of the labor situation in mid-May.” After May, there were only sporadic stories in the News-Tribune and other Iowa papers.

No explanation was given for these editorial decisions, but it’s worth considering that striking workers weren’t the ones buying the ads that newspapers relied on for revenue.

***

Whatever national impression the BWPU strike in Muscatine made was quickly eclipsed when workers at textile mills in Lawrence, Massachusetts began to walk out of their factories in January 1912.

The walkout was sparked by a pay cut, but the reasons it grew into a strike of 20,000 men, women and child laborers went beyond just meager pay. They wanted better working conditions, and they demanded to be treated with respect.

Conditions in the factories were horrific, but that didn’t engender much public sympathy. The strikers were mostly immigrants, almost half had been in the country for less than five years. These were exactly the workers that made the AFL and the WTUL uncomfortable.

The IWW quickly assumed a leadership role. The Wobblies, as they were known, believed in “one big union” of all workers, no matter where they were born or the color of their skin. The Wobblies were political radicals who wanted workers to take power in the workplace and replace the rich as the people who set the rules for society.

The strike met with fierce resistance, but in late February, police working on behalf of the factory owners went too far. They attacked a group of women strikers and their children. Public outrage exploded across the country. President William Howard Taft condemned the brutality. Congress launched an investigation. Normally anti-union newspapers turned sympathetic. Within weeks, the factory owners agreed to most of the strikers’ demands.

As workers were celebrating in Lawrence, the strike in Muscatine was sputtering to a close. Workers couldn’t hold any longer, and went back to the factories. The BWPU continued to exist, but only on paper.

It would take 20 years and the election of the union-friendly Franklin Roosevelt for union sentiment to stir again in Muscatine, but by then it was too late. Plastic buttons became the standard in the 1930s, demand for pearl buttons nosedived. All the factories in Muscatine closed.

All that remained from the city’s industrial heyday were clams and the quickly fading public memory of one of Iowa’s biggest strikes.

This article was originally published in Little Village’s April 2023 issues.