The Blind Boys of Alabama’s decades-spanning career speaks to both the universal human condition — we are all just passing through this world, searching for connection — and the very specific experience of being Black and disabled in America.

This venerable gospel group endured brutal Jim Crow racism, embraced the defiant optimism of the Civil Rights movement, survived the specter of Cold War nuclear annihilation, witnessed the fall of the Berlin Wall and have had their voices transported through every audio medium that has existed, from radio and vinyl records to streaming in the internet age. The embodiment of living history, the Blind Boys of Alabama keep past musical traditions alive while reinventing gospel music for the 21st century.

“Music is the one thing that can bring people together,” longtime group member Ricky McKinnie told me. “When you’re sad, music can help you break through that, and when you’re feeling good, music is the thing that can make you feel better. So, we realized that as long as our music touches people, we’re gonna keep on singing, because that’s what it’s all about.”

The Blind Boys formed as the Happy Land Jubilee Singers at the Alabama Institute for the Negro Blind in the late 1930s. They changed their name after a Newark, New Jersey promoter booked them in a “Battle of the Blind Boys” with another visually impaired gospel group from Mississippi. Seizing on the ensuing publicity, the two groups changed their names to the Blind Boys of Alabama and the Blind Boys of Mississippi, respectively.

For decades, the Blind Boys of Alabama were led by founding member Clarence Fountain, who passed away in 2018. Today, the gospel ship is steered by McKinnie, who was born in 1952 and joined the group in 1989. They had been part of his life for as long as McKinnie can remember because his mother was gospel singer Sarah McKinnie, whose path often crossed with the Blind Boys of Alabama on the southern touring circuit known as the gospel highway.

“That’s how I met Clarence Fountain,” McKinnie said. “When my mom was singing with the Jean Martin Singers out of Atlanta. She sang with gospel groups throughout the years, so when I was a kid, I would see the Blind Boys at the gospel concerts and enjoyed them, and eventually met all of them.”

“Back during Jim Crow,” he continued, “we’d stay at a friend’s house when we were touring, and we would have to eat at that friend’s house because we couldn’t get served in restaurants. There were a lot of times we’d go to the gas station, and they wouldn’t want to give you gas. So, it was a trying time, but we also had good times.”

McKinnie started out playing drums with a gospel group in his hometown of Atlanta, and when he was about 17, he got a call from Troy Ramey, who asked him to sing with the Soul Searchers. He cut his first major recording with the Soul Searchers before joining the Gospel Keynotes out of Texas, and during that time McKinnie sang on five records — including one that went gold, Reach Out, and another that went platinum, Destiny.

He began losing his sight due to glaucoma around the age of 20, and by the time Reach Out was released in 1975, McKinnie was completely blind. Three years later, he formed the Ricky McKinnie Singers with his mother, youngest brother and eldest brother. They toured as a family for many years, though he also became part of a much larger community that formed on the gospel highway.

“Back in the early days, the Blind Boys of Alabama were like family to me,” McKinnie said. “Clarence Fountain was a good guy. I loved him, and I respected him. All the original guys, they all knew me because I had been around them all my life, since I was a little boy. So, we would just be like one big happy family. Even though I was in the Gospel Keynotes in Texas, I had the opportunity to play drums with other groups, including the Blind Boys. So, even though I didn’t join them until 1989, I’ve always been a part of that group in one way or other.”

McKinnie is one link in an unbroken circle much bigger than himself or any other past or present member. He joined the Blind Boys of Alabama during an uptick in their career that had followed a long period of dwindling fortunes in the 1960s and 1970s, when many gospel fans and singers shifted their attention to secular forms of Black popular music like soul and funk.

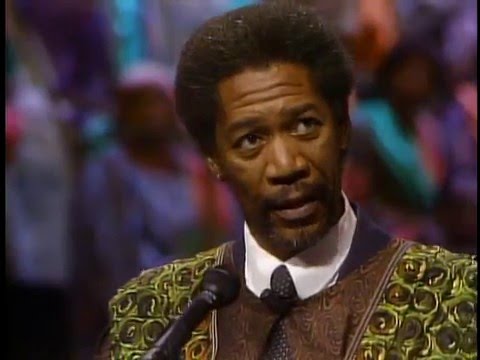

The Blind Boys of Alabama had primarily played in churches and community centers during the first four decades of their existence, until 1983, when they were cast in an African-American adaptation of Sophocles’ tragedy Oedipus at Colonus, retitled The Gospel of Colonus. The group collectively portrayed the blinded Oedipus, Morgan Freeman played The Messenger, and the show won an Obie for Best Musical in 1984 — after which it moved to Broadway for a successful run that gave the Blind Boys of Alabama their first real taste of mainstream success.

Since the turn of this century, they have released a string of critically acclaimed records on Peter Gabriel’s Real World label and have performed with a wide range of musicians, from Gabriel and Lou Reed to Prince and Stevie Wonder. Their cover of Tom Waits’ “Way Down in the Hole” was used as the theme song for The Wire when that groundbreaking HBO series launched in 2002. The Blind Boys of Alabama’s most recent album, Echoes of the South, was named after the Birmingham, Alabama radio program that hosted their first professional performance in 1944.

“I’ve been with the Blind Boys through all of the major events that they’ve had,” McKinnie said. “For every Grammy Award, and for the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Helen Keller Award. We performed at the White House three times for President Clinton, President Bush and President Obama.”

“Right now, we are getting ready to do a PBS special with the Alabama Symphony Orchestra, and Echoes of the South was nominated for three Grammys in three different categories. In March, a book on the Blind Boys of Alabama book is coming out, called Spirit of the Century, so we have three major days in the next three months.”

The respect and accolades that the Blind Boys of Alabama have earned is certainly gratifying, but what matters most to McKinnie and his bandmates is the music itself and the deeper truths that underpin the songs they sing.

“If you feel bad, you come to a Blind Boys show and you’re going to feel glad,” McKinnie said. “If you feel like clapping your hands, if you feel like doing a dance, or you feel like singing a song, we’re exactly what you need. So, don’t miss it when the Blind Boys are back in town!”

Kembrew McLeod bought his first Blind Boys of Alabama album roughly 33 1/3 years ago, and he has been a fan ever since. This article was originally published in Little Village’s February 2024 issue.